Forensic science and native animal conservation

The illegal laundering of wildlife is the second greatest threat to global species loss after habitat destruction. Despite this, the global billion-dollar industry lacks regulation and robust forensic methodology for detecting and monitoring criminal activity. The Convention of International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) and TRAFFIC have recently identified huge discrepancies between the number of ‘captive-bred’ animals being exported overseas and the actual captive breeding capabilities of the species and the regions.

One example is the iconic short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). Short-beaked echidnas are notoriously hard to breed in captivity. Even with a team of experts, Taronga has produced 3 puggles in 30 years. With similar low success rates across leading institutions, and high neonatal fatality, how does Indonesia manage to export so many ‘captive-bred’ echidnas each year under a yearly quota of 50? The answer, sadly, is illegal poaching of wild populations.

Up until now there has been no scientific tool available to test if an animal has been raised in captivity or taken from the wild. Past methods have relied on vague descriptions of colours and other subjective indexes, but nothing that can prosecute the traders. Taronga’s Forensic team has developed an exciting, novel method that uses stored elemental signatures in keratinous tissues (quills, hair, scales, scutes and fur) to identify the origin of the animal. The basis of our hypothesis is an animal that has been foraging in the wild will have a permanent signature that reflects the diversity of naturally available prey items, while an animal that has been raised in captivity will have a signature that reflects a simple commercial feed or low diverse diet.

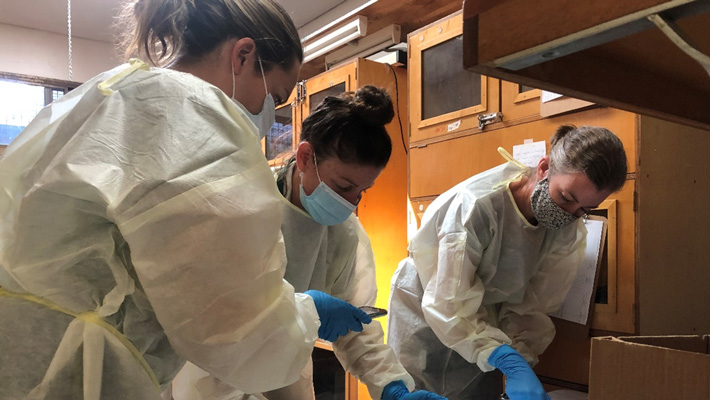

Our forensic team, comprising scientists from Taronga, University of New South Wales (UNSW), University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANTSO), tested this hypothesis, and through a combination of stable isotope analysis, nuclear x-ray fluorescence and machine learning models achieved assignment of origin with 100% accuracy. View the published results.

The team, with support from our philanthropic donors, have their sites set on tackling the most trafficked species out of Australia; Shinglebacks, Blue-tongue lizards and fresh-water turtles.